Tensions

Steve could not deal with the market failure of his baby. He continued to behave as if he had saved Apple, treating non-Mac employees with deference in Cupertino. People felt he spoiled the Mac team, buying them a BMW motorcycle and a Bosendorfer grand piano with his personal money, while the company was still alive thanks only to Apple II sales (the truth was that Macintosh engineers were paid the same or even less than their counterparts).

There was increasing resentment building up against Steve Jobs at Apple. The honeymoon with CEO John Sculley was over: the two men increasingly criticized one another in their inner circles. Even Woz, who felt insulted by the treatment the Apple II team received, left the company in February 1985. He openly criticized the management in Cupertino: this was a PR disaster for the firm.

There was increasing resentment building up against Steve Jobs at Apple. The honeymoon with CEO John Sculley was over: the two men increasingly criticized one another in their inner circles. Even Woz, who felt insulted by the treatment the Apple II team received, left the company in February 1985. He openly criticized the management in Cupertino: this was a PR disaster for the firm.In April 1985, the board discussed re-organization plans for the company. Everyone agreed there should be a new manager for the Mac team, namely Apple France executive Jean-Louis Gassée. Jobs even accepted the idea for a while, thinking of running a new R&D department instead. But he was outraged when Gassée asked for a written guarantee of his promotion.

To him, it became a personal war with Sculley. While the CEO was away on a business trip, on May 23 1985, Steve gathered some of his top aides, telling them Sculley wanted him out of his own company. The next day, Sculley heard of the scheme and canceled his trip. He confronted Steve in front of the other Apple executives. After hours of intense discussions, they simply couldn’t find a solution to the conflict between the two men. Steve said he would take a vacation until they were done with the re-organization, and left. It was only a few days later, on May 28, that Sculley informed him that the board had decided on a new org chart, which did not include him at any managerial position. Steve’s conviction the board would support him had proved wrong: he had lost the final battle.

At 30 I was out. And very publicly out. What had been the focus of my entire adult life was gone, and it was devastating. I really didn't know what to do for a few months. I felt that I had let the previous generation of entrepreneurs down — that I had dropped the baton as it was being passed to me. I met with David Packard and Bob Noyce and tried to apologize for screwing up so badly. I was a very public failure, and I even thought about running away from the Valley.

Stanford Commencement Address, 12 Jun 2005

Experimentations

During those four months, from May to September 1985, Steve was still chairman of the board — he was not fired from Apple, contrary to popular belief. But he had a lot of times on his hands, and tried hard to find what he was going to do next.

He traveled to Europe, advocating Macintosh to French universities, biking around Tuscany, and thinking of settling in the south of France. He went to the Soviet Union to preach the benefits of personal computing and asked NASA if he could ride the Space Shuttle. He even thought of running for the office of governor of California, seeking advice from his friend Jerry Brown. But none of these endeavors could really absorb his energy and his continuing passion for computing.

He also looked for places to invest in. One of his very good friends from Xerox PARC, computer pioneer Alan Kay, told him about an iconoclastic group of computer graphics developers north of the Bay Area, whose parent company, Lucasfilms’ Industrial Light & Magic, was trying to get rid of.

The genesis of Pixar

The founding fathers of Pixar were researchers Ed Catmull and Alvy Ray Smith, who, as early as the 1970s, shared a dream of making animated movies with computers. Yet they knew it would take at least a decade before their vision could materialize, given the necessary computing power to handle such complex operations. So they just got together and waited for the technology to evolve.

Catmull and Smith slowly put together a core team of computer graphic pioneers that also believed in computer-animated films. Among the first members were computer scientists Ralph Guggenheim and Bill Reeves. John Lasseter, a brilliant animator from Disney, joined them in 1984. The group moved from one benefactor to the next since its creation; in 1985, they belonged to George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic (ILM).

Yet the Star Wars filmmaker was trying to sell the division. He needed money after his divorce, and, more importantly, he did not share the team’s vision. He just wanted to use 3-D animation for special effects in movies.

In addition, at the time, Pixar was working on a graphical workstation, a very powerful computer dedicated only to processing visual data. They had also started developing their own 3-D computer language, RenderMan. The department was clearly evolving outside of Lucasfilm’s realm, and that’s why they were looking for a new patron.

Steve toured the ILM lab and was mightily impressed. He compared this experience with his revelation at Xerox PARC six years earlier, when he was first shown the graphical user interface. Yet the price tag was too high: $30 million. He turned Lucas down, but asked to be given a call if the offer got cheaper.

A new venture

As the story goes, Steve Jobs was still looking for new directions in life when he met with a friend of his, Nobel Prize Paul Berg, from Stanford University. Berg told him of his work on DNA, and asked him whether the molecules could be simulated on computers. The answer was no, not yet anyway... this gave Steve the idea of starting a new company. He would build a high-end computer aimed solely at the higher education and research markets. He asked around and found out the general consensus was a need for a so-called 3M machine — a computer that could hold one megabyte of memory, perform one million instructions per second, and display one million pixels on a screen.

Since he was still at Apple, he decided to inform the board of his decision. On September 13 1985, he described his plan. The board seemed enthusiastic at first, even willing to invest in the chairman’s new venture. But when Steve announced who would join him in his new company, called Next, they turned bitter: he would go away with Bud Tribble, the first Mac programmer; George Crow, a key Mac hardware engineer; Rich Page, who had supervised almost all of Lisa’s development; Dan’l Lewin, who had made the Apple University Consortium possible; and Susan Barnes, a Wharton alumnus with a MBA in finance. These were not “low-level” people, as Steve had presented them! Apple felt threatened, especially since they were themselves working on a 3M machine code-named “Big Mac”.

This was the coup de grâce for Steve. On September 17, he announced his resignation from Apple to an assembly of stunned journalists gathered at his mansion in Woodside.

NeXT Inc.

Next did not start easily. The minute it was created, the six co-founders found themselves sued by their former employer, Apple. The fruit company was accusing them of stealing their technology.

As a result, for its first year or so of existence, the new company could not work on any product in particular, since there was a chance they would lose the trial and give all the technologies they had worked on back to Apple.

In the meantime, Steve Jobs set up to build the perfect company.

The Next co-founders outside Steve’s mansion in Woodside.

From left to right: Steve Jobs, George Crow, Rich Page,

Susan Barnes, Bud Tribble and Dan’l Lewin.

From left to right: Steve Jobs, George Crow, Rich Page,

Susan Barnes, Bud Tribble and Dan’l Lewin.

The perfect company

He started by doing one of the things he was best at doing: recruiting. He hired only extremely bright and competent people. At one point Next bragged that even their receptionist was a Ph.D.! There was incredible hype around Steve’s new venture. It seemed like the whole Valley wanted to work at Next — even though it was considered “a leap of faith” (since nobody knew what they would have to work on eventually). Among its first employees was Avie Tevanian, a software genius who was still a student at Carnegie Mellon University when Steve met him. He was working on a UNIX kernel called Mach; Steve told him that if he joined Next, his invention would run on millions of computers in a few years time.

You basically had to meet everyone in the entire company and they all had to give you the thumbs-up. It really felt like a fraternity. Everyone had to love you. So the feeling you got was that anyone who got through had to be ‘the best of the best’

an early NeXT employee quoted in Alan Deutschman's The Second Coming of Steve Jobs

Next treated its employees in a pretty unique fashion in Silicon Valley. First, there were only two levels in salary for a long time: senior staff earned $75,000 a year, and the rest earned $50,000. It gave the place sort of a communal feel, a community of super-bright people, not a tech start-up driven by greed. Other perks included health club memberships, counseling services, emergency loans, and free fresh juice. Keep in mind the company still had no revenues to speak of during those early years — it was still operating with Steve’s pocket money.

Steve also went and looked for a logo and a corporate identity for his new venture. He found both after he asked who was the best logo designer on the planet, and was introduced to Yale art professor Paul Rand. Rand designed a logo for no less than $100,000, and came up with the name NeXT, with a conspicuous lowercase “e”, that was supposed to stand for: “education, excellence, expertise, exceptional, excitement, e=mc2...” (see this video about it).

Finally, Steve proved not too parsimonious either when it came to NeXT’s headquarters. One of the company’s first ten employees was actually Tom Carlisle, a full-time interior designer. They settled in one of the most expensive areas of the Valley, the Stanford Industrial Park, not far from Xerox PARC. Carlisle furnished the place with glass walls and beautiful Ansel Adams prints, and set up a common area with hardwood floors that included a kitchen with granite counter tops and a lounge with U-shape sofas that sat 12.

Money matters

After his departure from Apple, Steve had sold almost all of his stock out of disgust. So by early 1986, he was sitting on more than $100 million, waiting for opportunities to invest. He got a call from Lucasfilm: they weren’t able to find any suitable buyer for the computer graphics team, so they dropped the price by two thirds. Steve agreed to pay the $10 million, and on January 30, Pixar was incorporated. It would turn out to be a money sink of his for years to come.

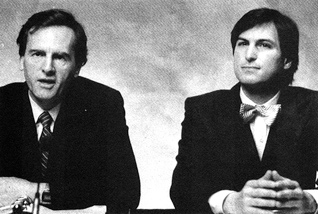

Steve Jobs with investor Ross Perot

But Pixar didn’t matter much — it was Steve’s “hobby”, as his heart was at NeXT. He let Catmull and Smith run their small team north of the Bay Area, while he spent his days in Palo Alto. Apple had just dropped its lawsuit against the startup, so they could finally start working on their computer for higher education.

Interestingly enough, Steve’s habits as an investor were quite the opposite of his affections for his companies. While he did not care about Pixar nearly as much as he cared about NeXT, he opened the company a line of credit that he would pay with his own money for several years. Pixar was always begging for Steve’s money as they barely had any revenues. On the other hand, he refused to fund NeXT solely with his own money. He started to look for outside investors early on.

A critical change occurred when, in November 1986, CBS aired a documentary called The Entrepreneurs which featured Jobs during NeXT company retreats. A watcher was millionaire Ross Perot, who was still immensely rich from selling his company Electronic Data Systems to General Motors. He was seduced and phoned Steve: “if you ever need an investor, call me.”

It was good news as NeXT was burning money at an incredibly fast rate. So the deal was quickly signed: in February 1987, they announced Perot invested $20 million in exchange for 16% of NeXT, while Steve kept 63% for himself. The company had no product but a t-shirt back then, yet it was already valued over $125 million! This is how powerful Steve Jobs’ name was in the mid-1980s. Ross Perot joined the board of directors together with Carnegie Mellon administrator Pat Crecine, a good friend of Steve’s. Not a very balanced board of directors indeed...

Personal life

Steve and Lisa circa 1989

There were crucial evolutions in Steve’s personal life as well. First, after years of research, he had finally found his biological family. His biological mother Joanne was still alive, and she had actually married his father a couple of years after Steve was born. They had given birth to a daughter, Steve’s biological sister, called Mona. Mona Simpson was a young yet accomplished writer who had just published a novel that earned her several literary prizes,Anywhere But Here. Steve was thrilled his sister was an artist: there was indeed art in his genes! He filled a bookshelf at NeXT with free copies of Mona’s book.

He also started to fully accept his 9-year-old daughter Lisa as family. She increasingly spent time at his home in Woodside, and he even took her to NeXT’s offices from time to time. He started to get deeply involved in her education.

Finally, he became more stable in his relationships and was thinking of marrying his girlfriend Tina Redse.

This whole period of Steve’s life is well documented in A Regular Guy, a novel by Mona Simpson which barely disguises Steve Jobs and Lisa as its main characters.

0 comments: